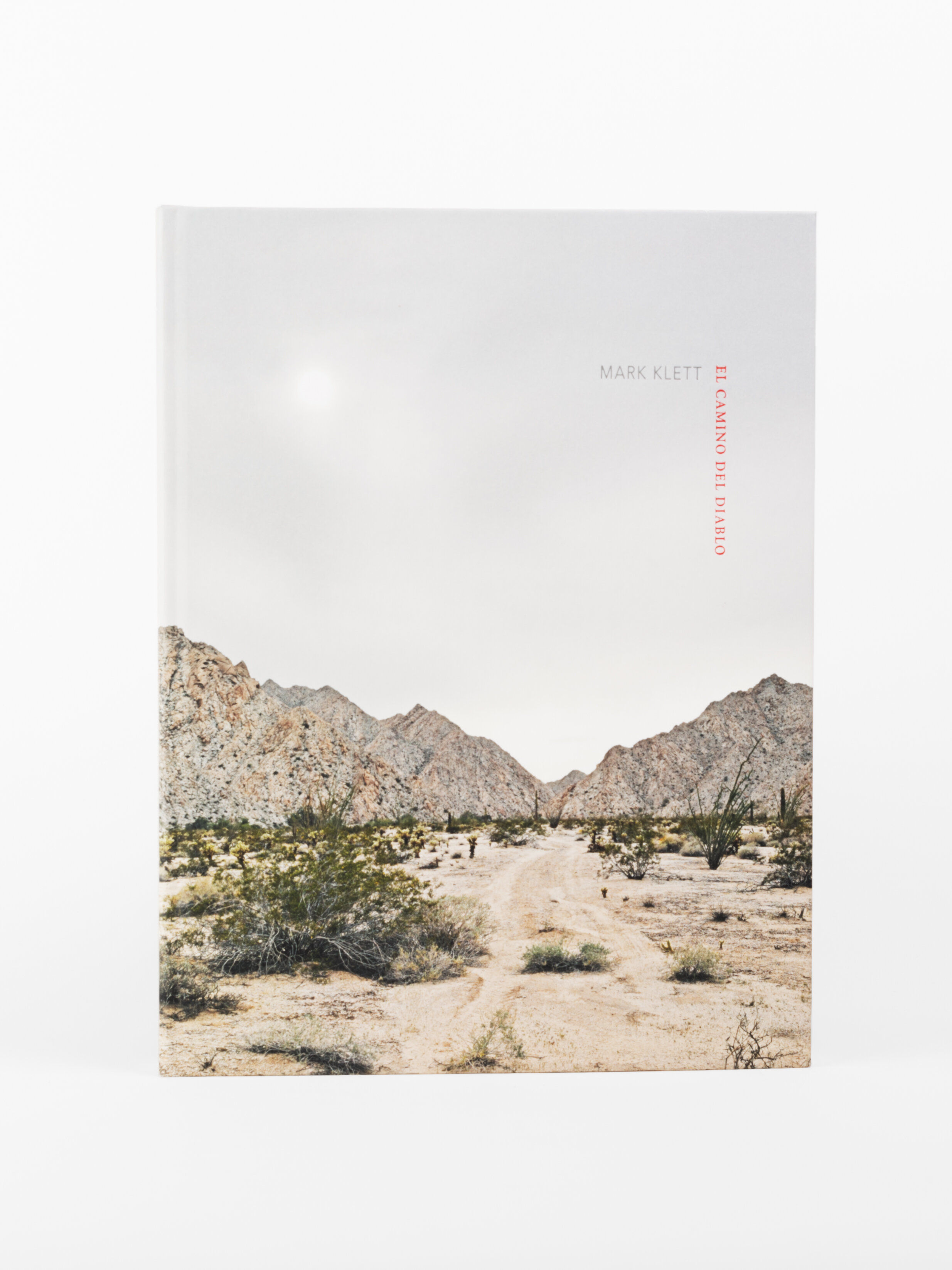

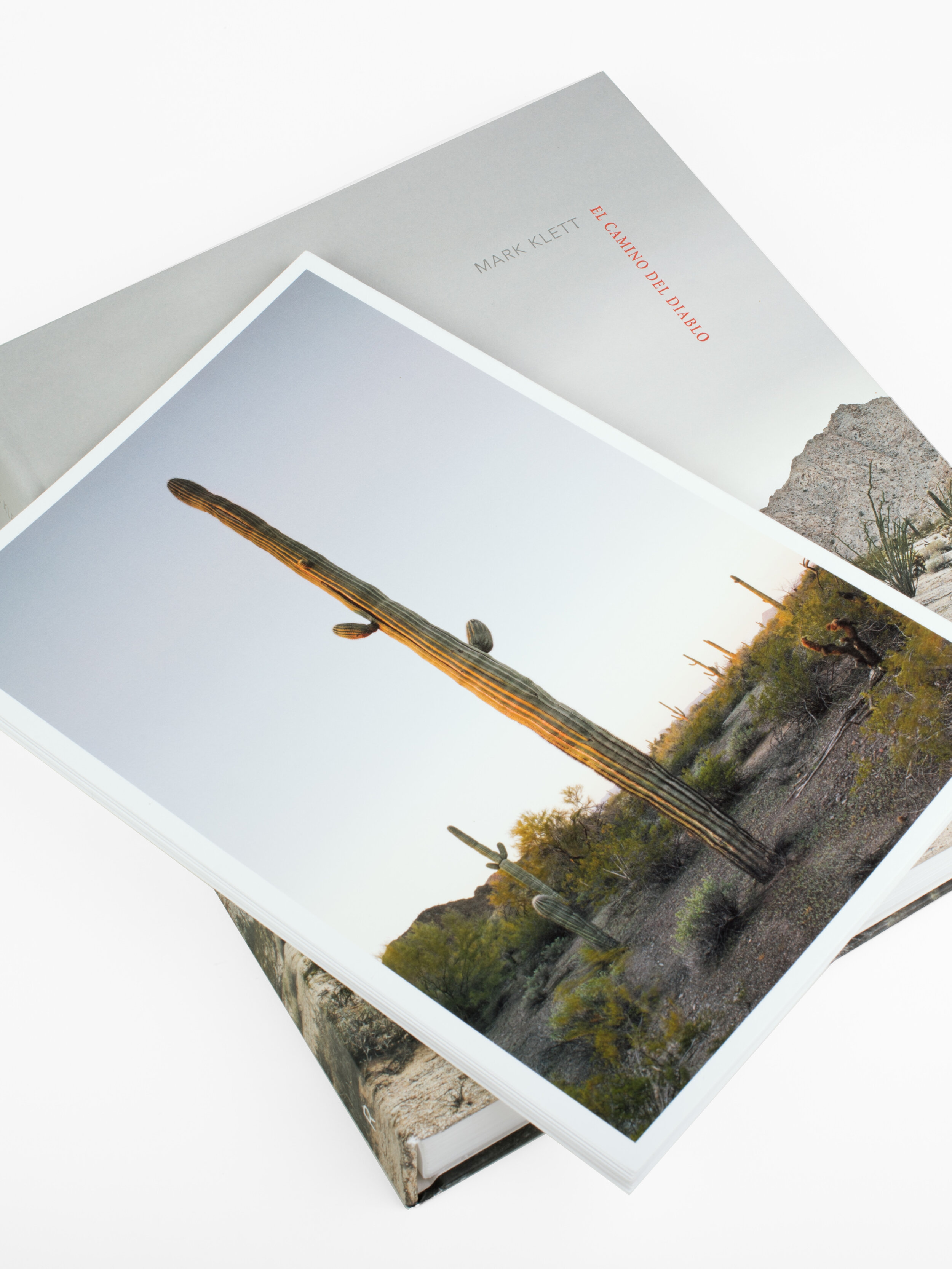

Mark Klett: El Camino del Diablo

He captures the spirit of the explorer’s dark, wide-eyed vision with a critical distance.

— Jordan G. Teicher, Photograph Magazine

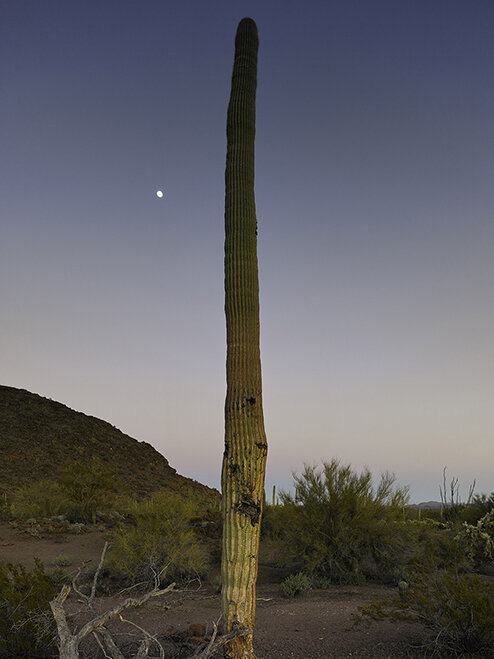

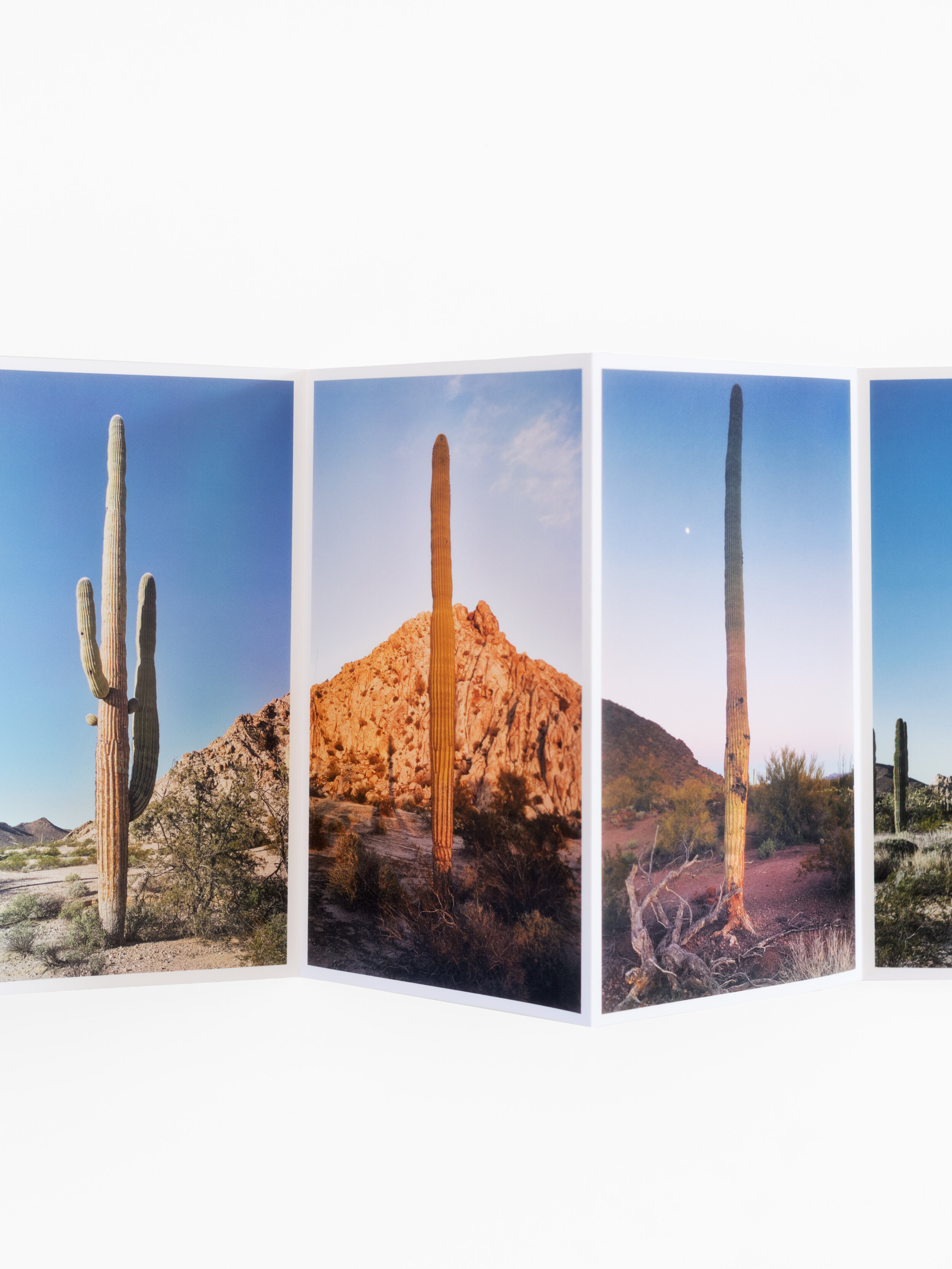

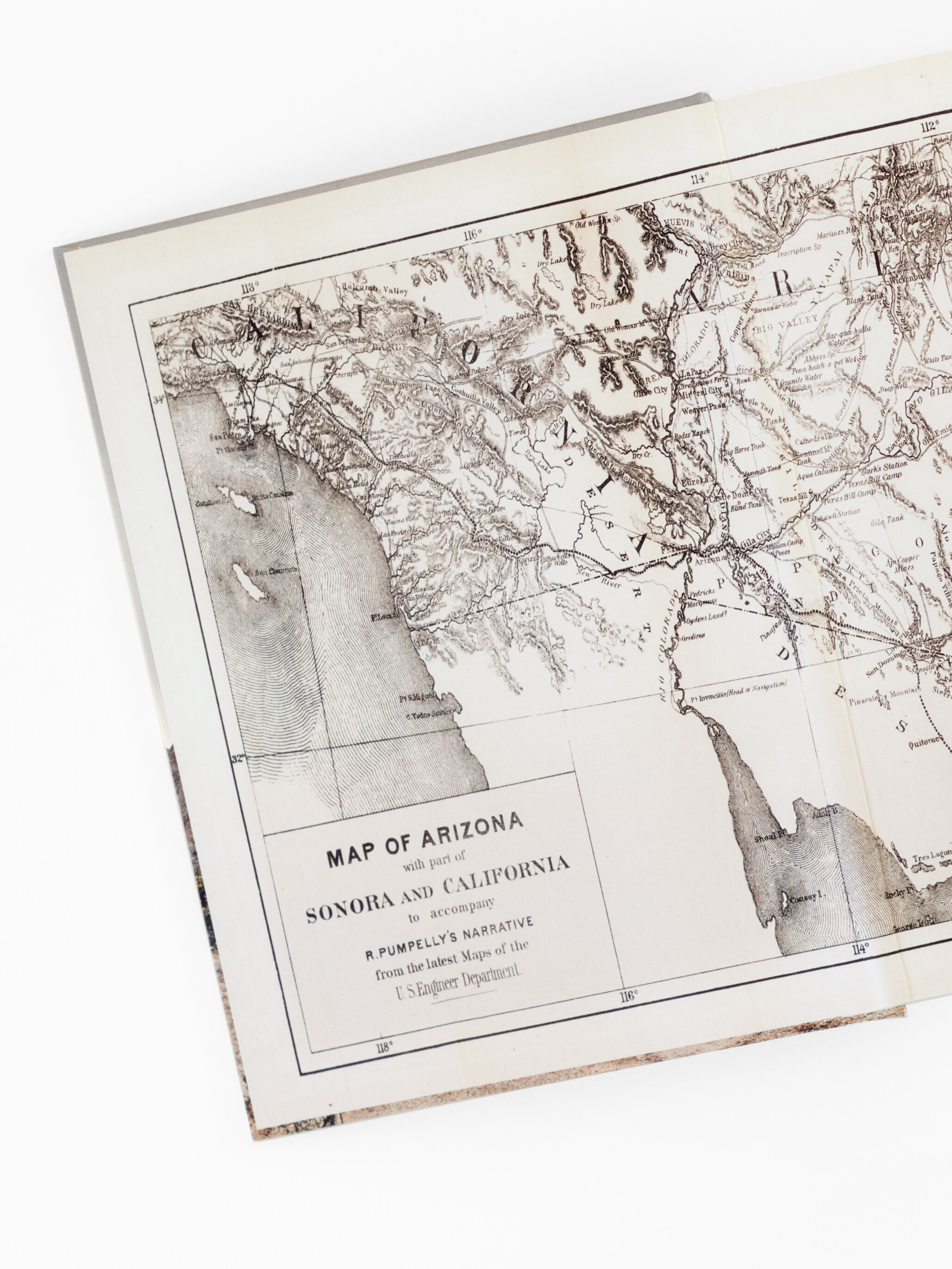

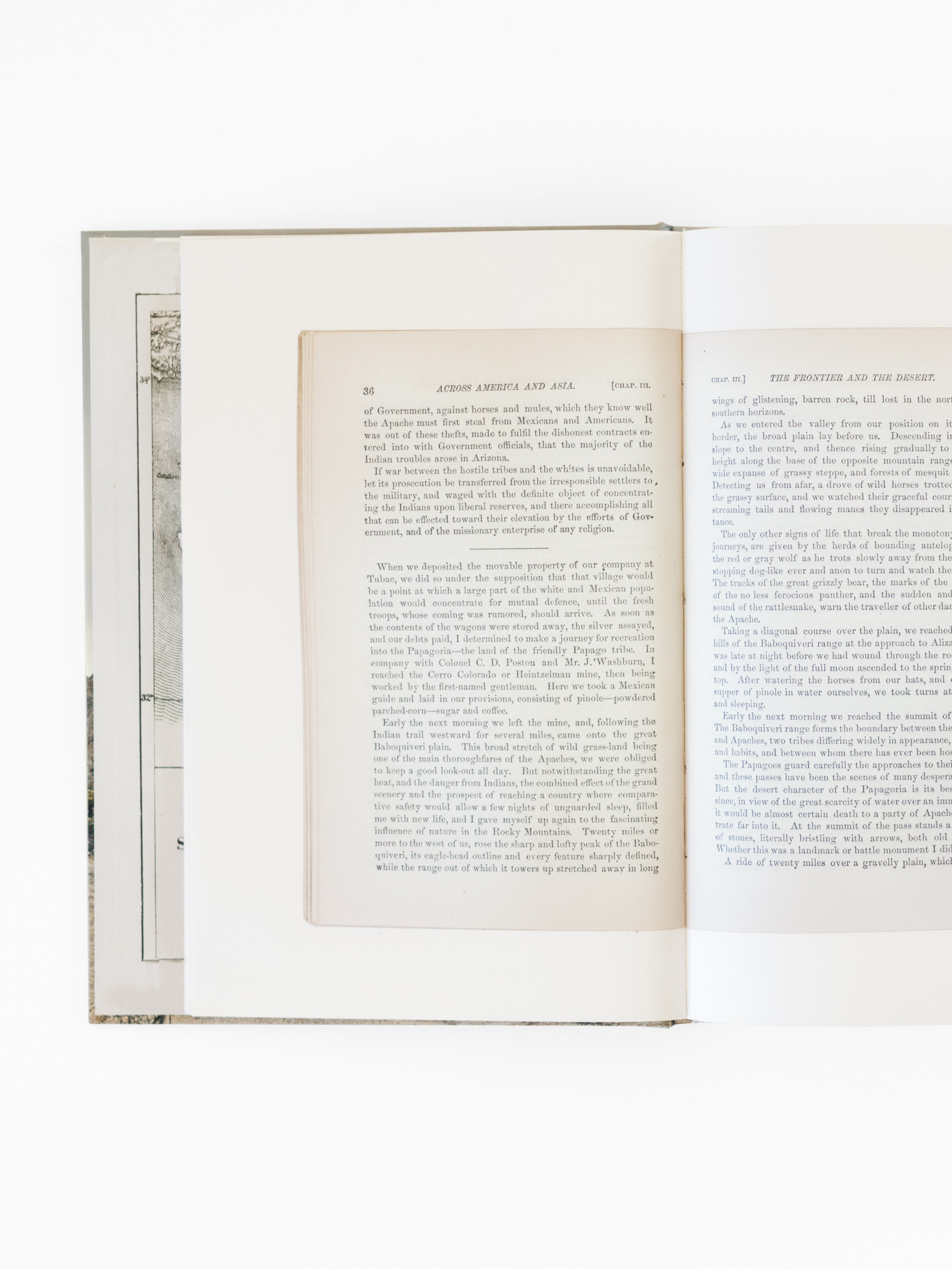

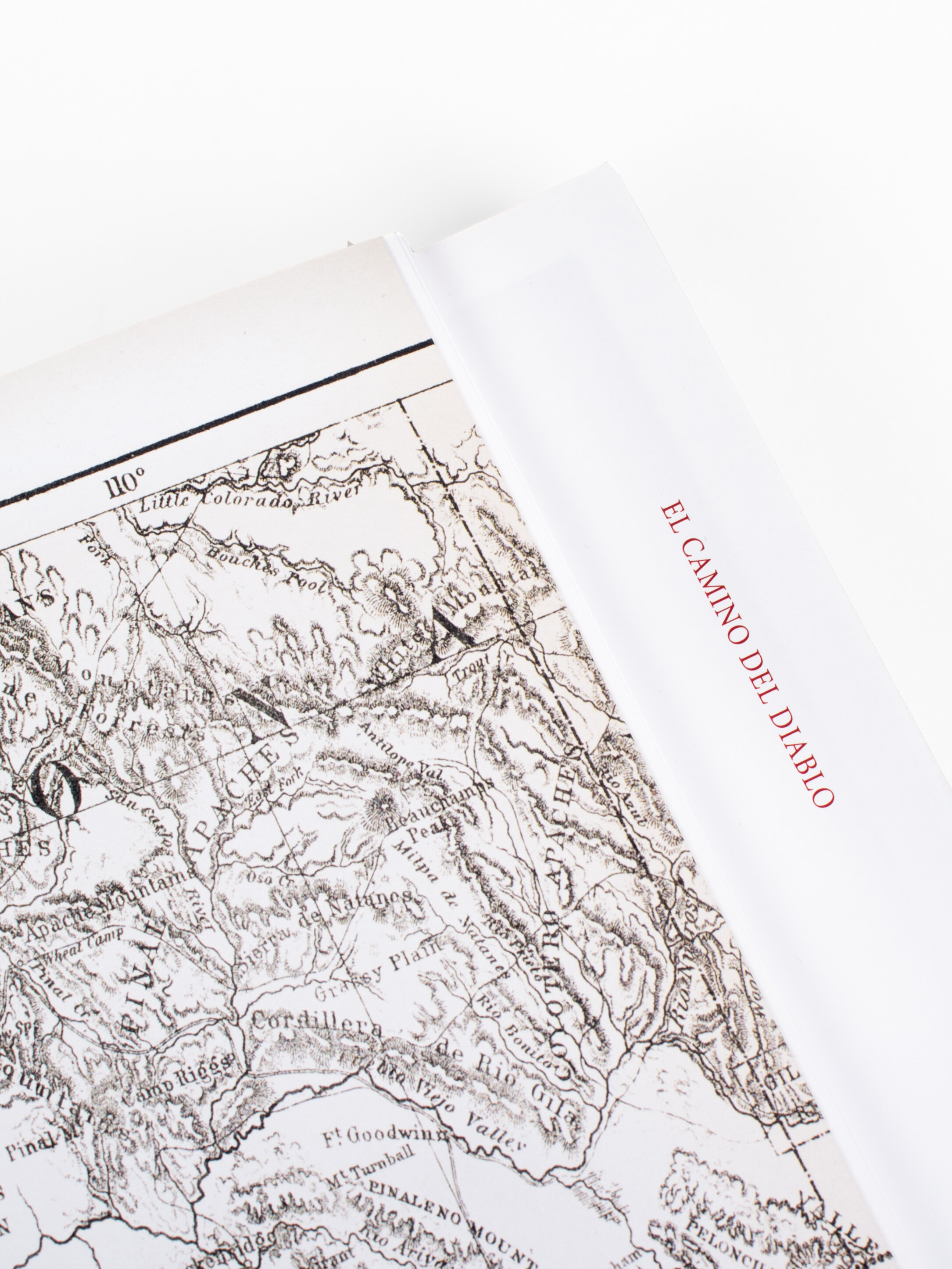

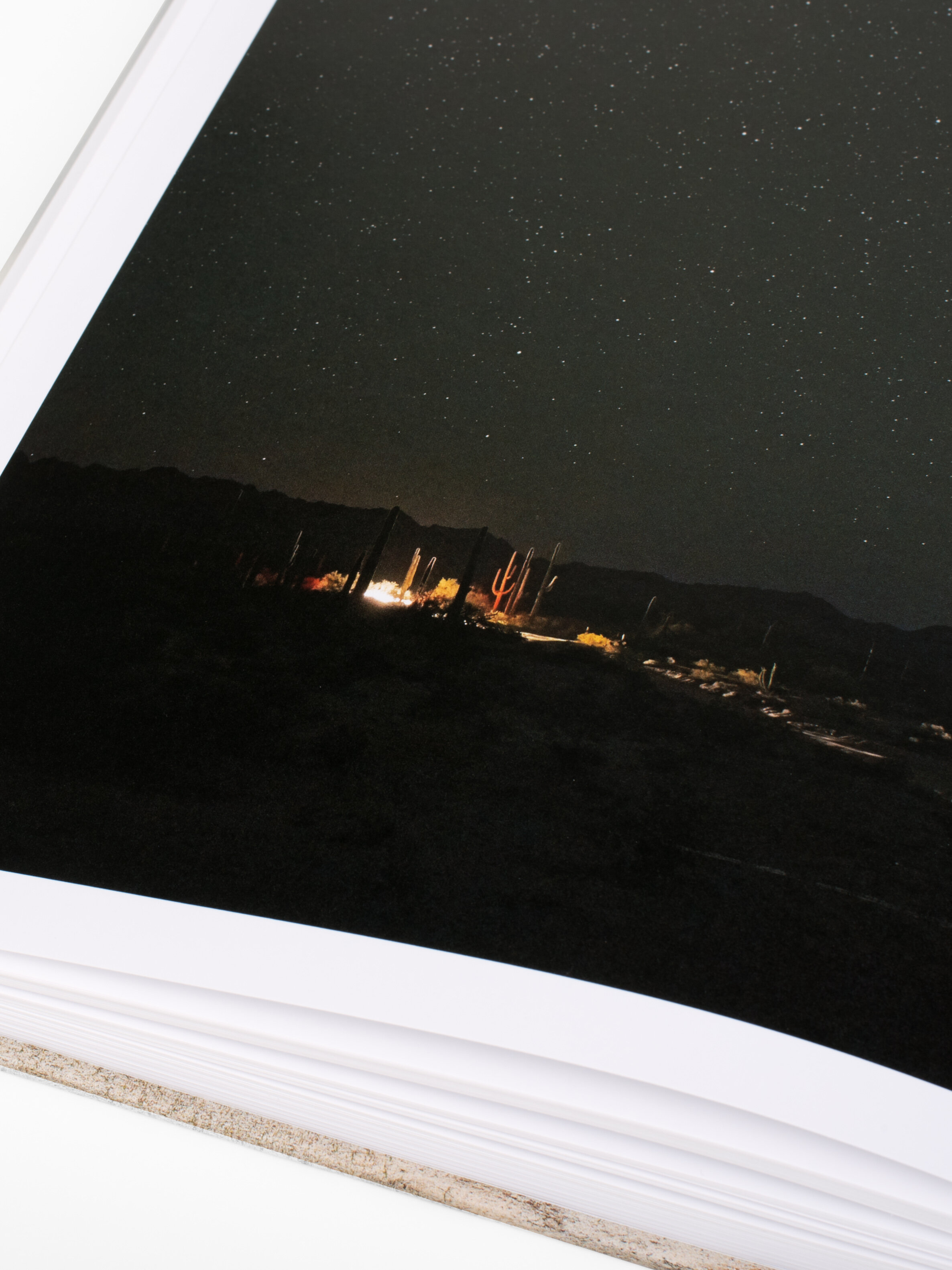

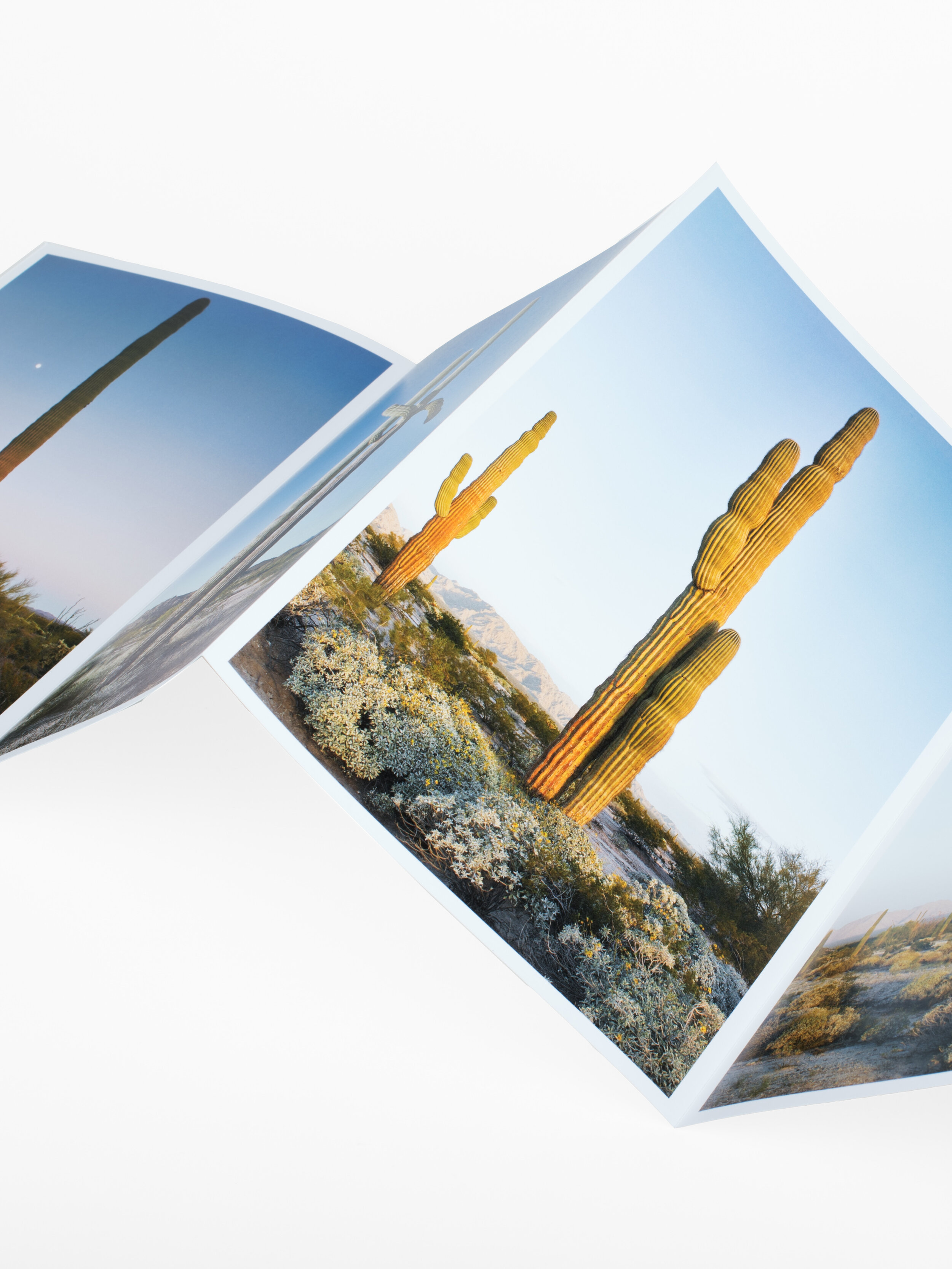

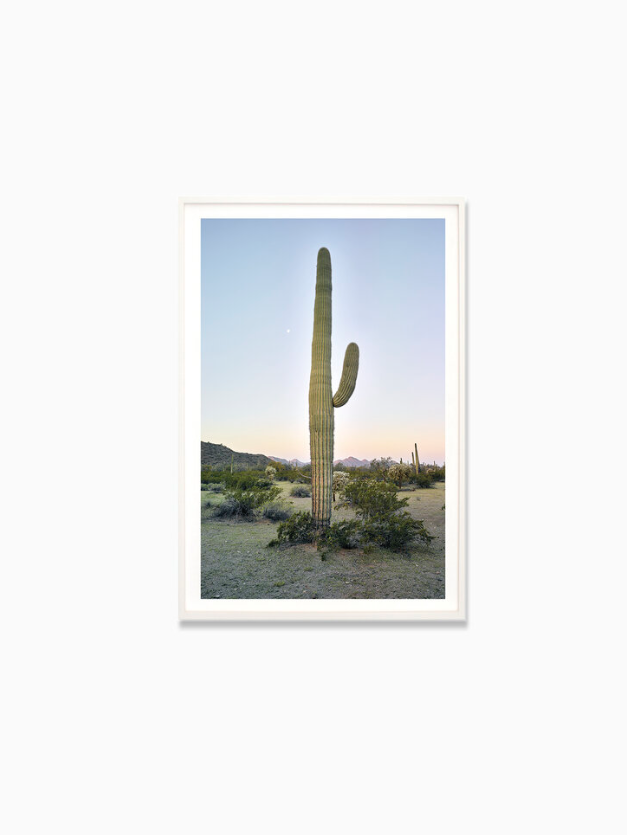

Much of Mark Klett’s work as a photographer has centered on a conversation with historical images. For this project, Klett worked only with the account of a young mining engineer named Raphael Pumpelly, who wrote of his journey through Arizona and Mexico in 1861 on the Camino del Diablo or “the road of the devil.” Pumpelly found the territory lawless and filled with danger. Mexican laborers working in the silver mines south of Tucson were perpetually killing their Anglo bosses, and the authorities were virtually non-existent. The Apache led constant raids and ambushes. Pumpelly escaped death several times, often by a matter of minutes. Traveling 130 miles of open desert, he proceeded with both apprehension of the dangers at hand, and appreciation of the natural beauty that surrounded him.

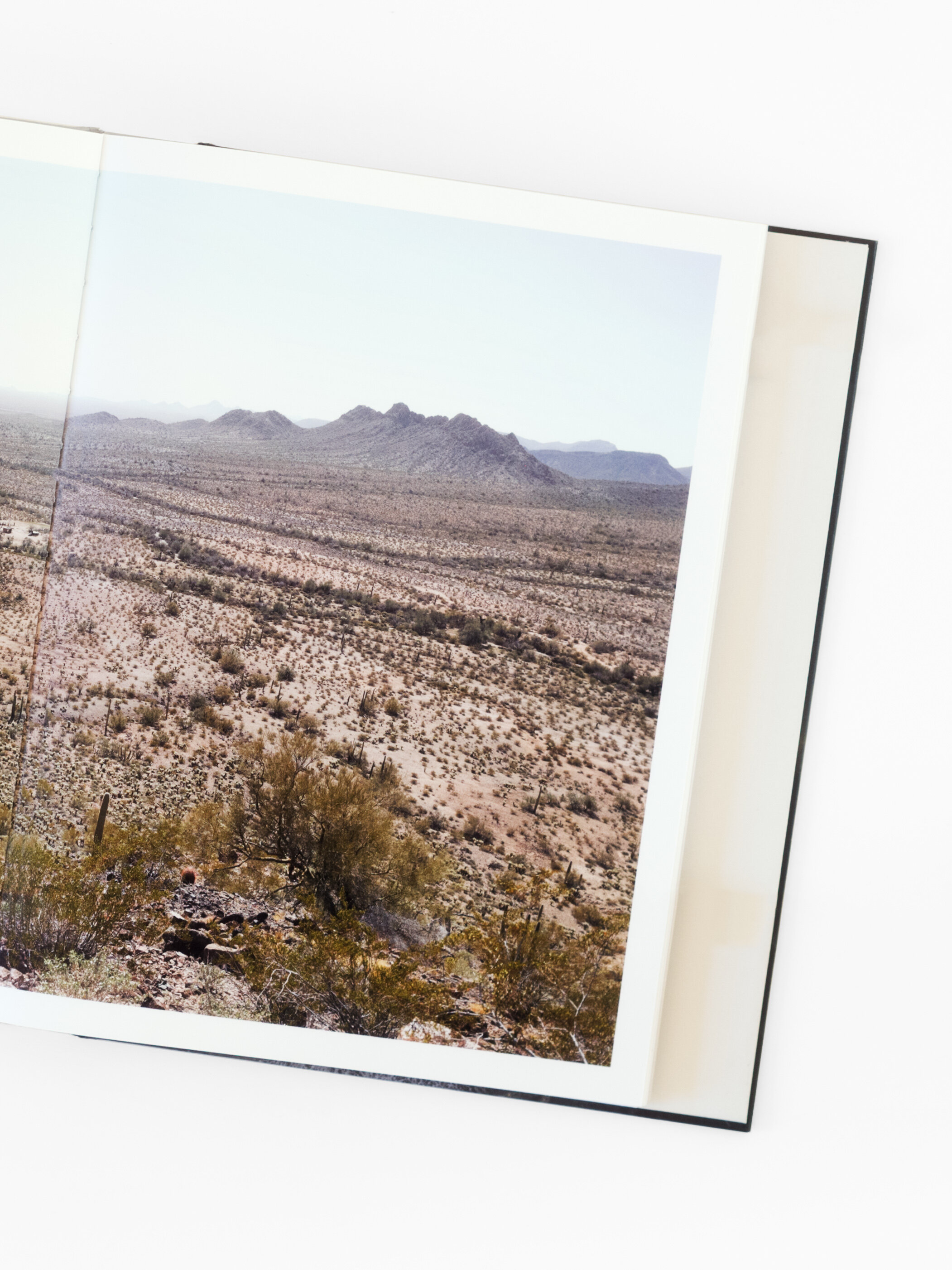

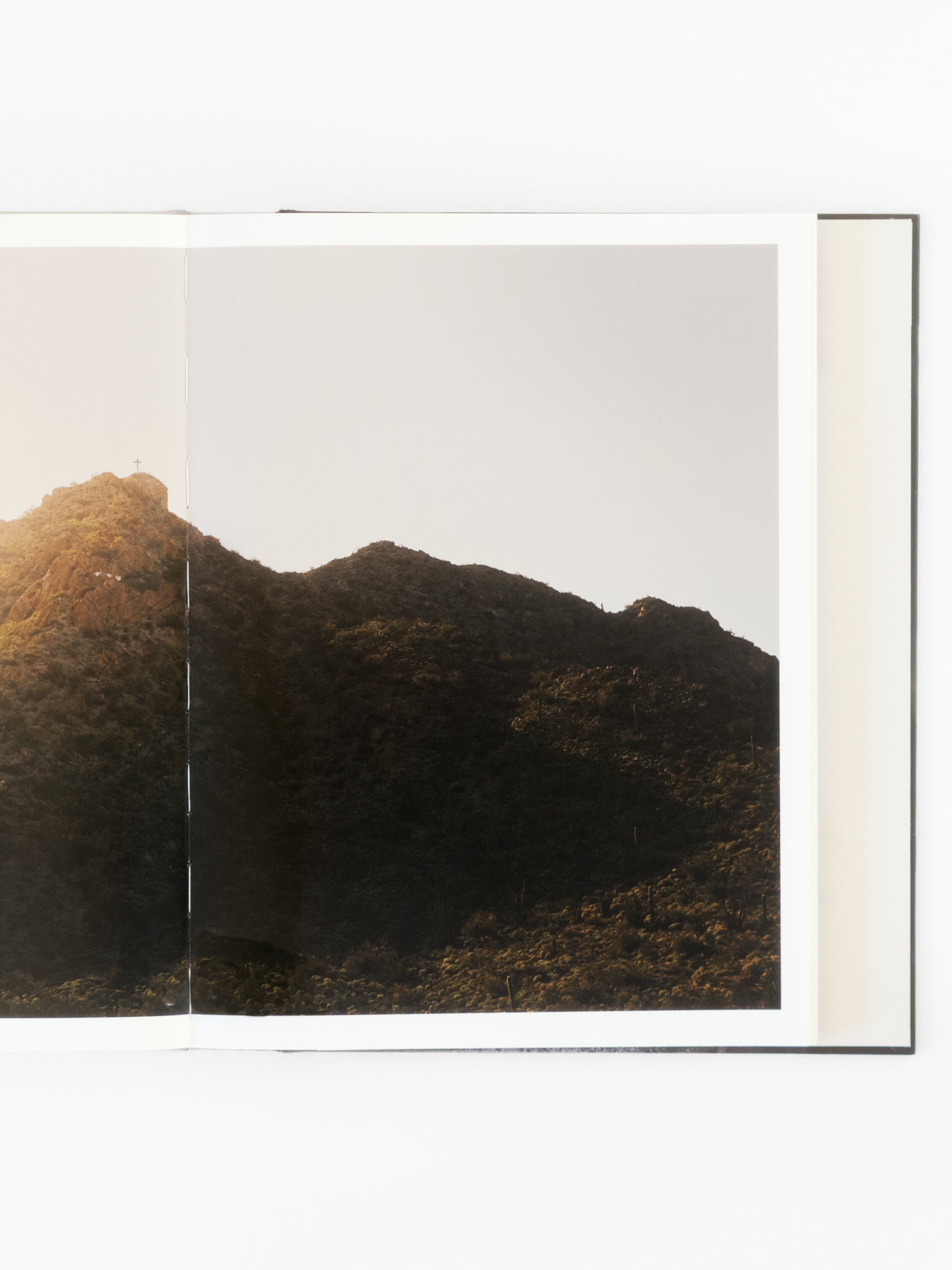

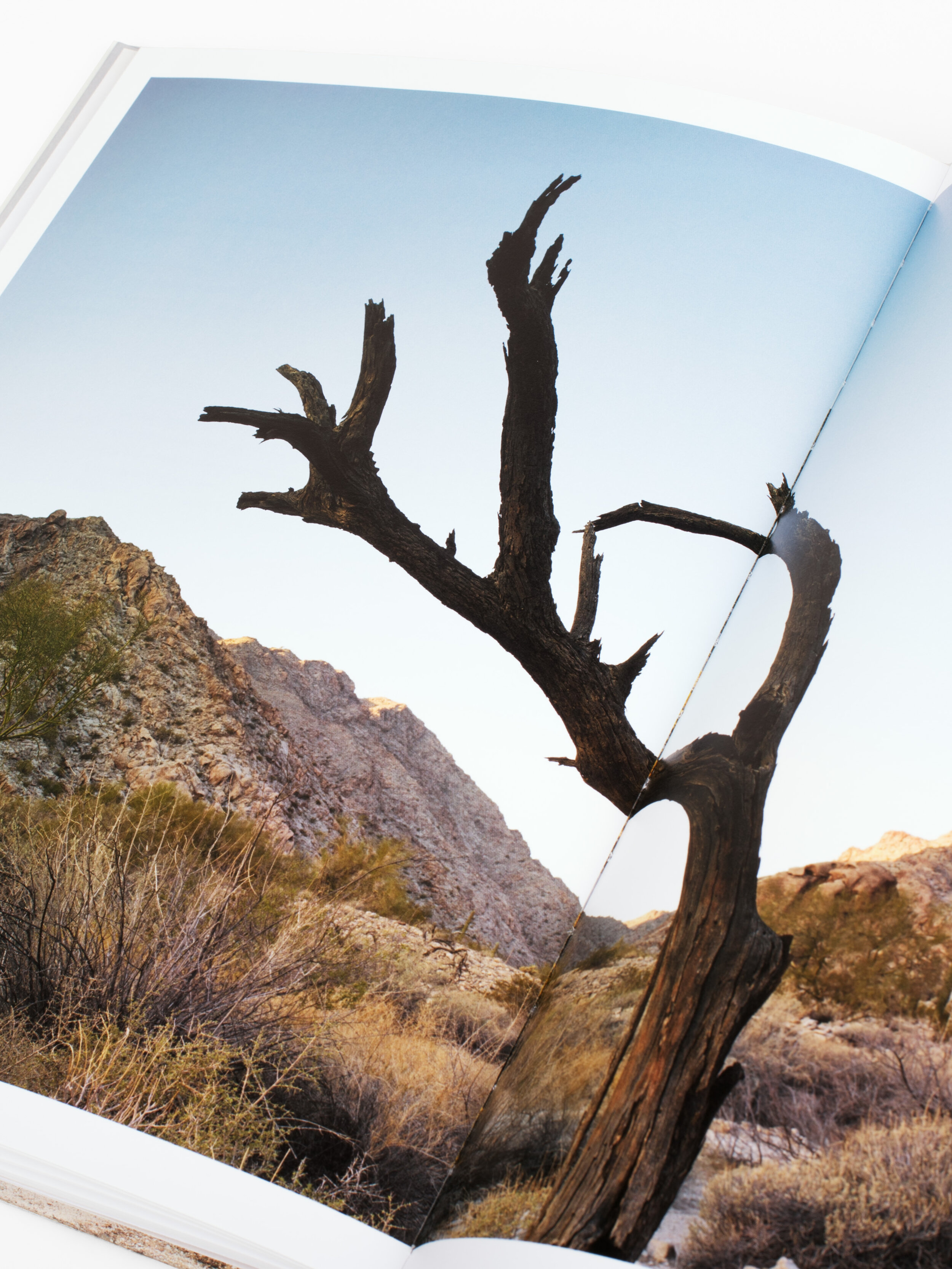

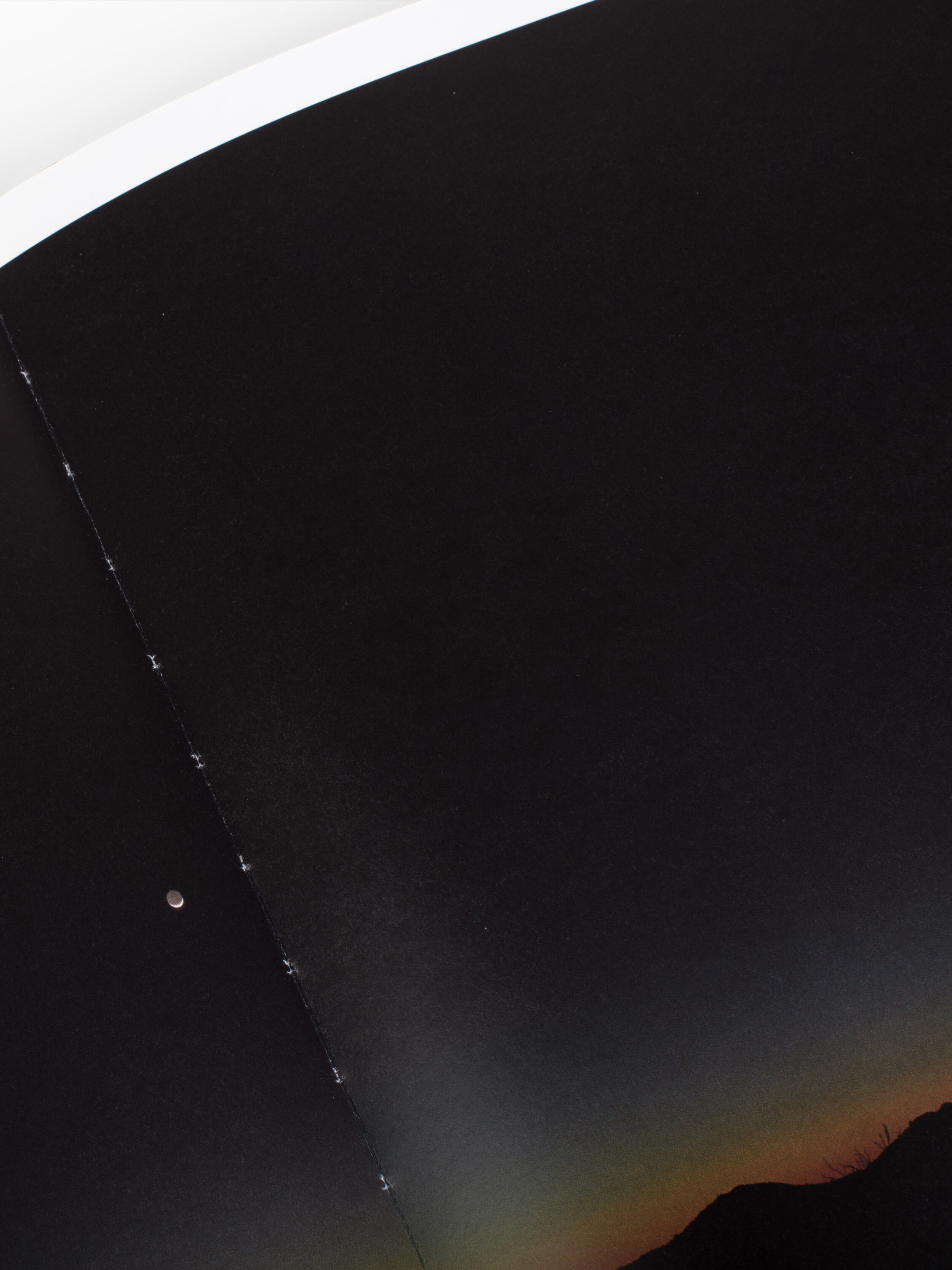

152 years later, Klett traversed the same route, making photographs in response to Pumpelly’s words. Unable to trace the engineer’s exact steps, Klett created images that are not literal references to specific places or events. Rather, he sought to produce a more poetic narrative to their shared experience of the Arizona desert, along the common route that connects the two through time.

Today, most of the Camino is located on the Barry M. Goldwater Bombing Range and the border is a militarized zone constantly patrolled by government agents and crisscrossed by air and ground forces practicing for war. Camino travelers often hide from detection, be they immigrants or drug smugglers moving North under the cover of night or the ruggedness of the terrain. Indian reservations create boundaries and mark other cultural divides. A hostile climate kills many who dare travel in hot weather and people die each year on the Camino, most from exposure. Yet the Camino also crosses one of the most beautiful and still wild regions of the Sonoran Desert.

Limited edition of this book available HERE

He captures the spirit of the explorer’s dark, wide-eyed vision with a critical distance.

— Jordan G. Teicher, Photograph Magazine

Much of Mark Klett’s work as a photographer has centered on a conversation with historical images. For this project, Klett worked only with the account of a young mining engineer named Raphael Pumpelly, who wrote of his journey through Arizona and Mexico in 1861 on the Camino del Diablo or “the road of the devil.” Pumpelly found the territory lawless and filled with danger. Mexican laborers working in the silver mines south of Tucson were perpetually killing their Anglo bosses, and the authorities were virtually non-existent. The Apache led constant raids and ambushes. Pumpelly escaped death several times, often by a matter of minutes. Traveling 130 miles of open desert, he proceeded with both apprehension of the dangers at hand, and appreciation of the natural beauty that surrounded him.

152 years later, Klett traversed the same route, making photographs in response to Pumpelly’s words. Unable to trace the engineer’s exact steps, Klett created images that are not literal references to specific places or events. Rather, he sought to produce a more poetic narrative to their shared experience of the Arizona desert, along the common route that connects the two through time.

Today, most of the Camino is located on the Barry M. Goldwater Bombing Range and the border is a militarized zone constantly patrolled by government agents and crisscrossed by air and ground forces practicing for war. Camino travelers often hide from detection, be they immigrants or drug smugglers moving North under the cover of night or the ruggedness of the terrain. Indian reservations create boundaries and mark other cultural divides. A hostile climate kills many who dare travel in hot weather and people die each year on the Camino, most from exposure. Yet the Camino also crosses one of the most beautiful and still wild regions of the Sonoran Desert.

Limited edition of this book available HERE

He captures the spirit of the explorer’s dark, wide-eyed vision with a critical distance.

— Jordan G. Teicher, Photograph Magazine

Much of Mark Klett’s work as a photographer has centered on a conversation with historical images. For this project, Klett worked only with the account of a young mining engineer named Raphael Pumpelly, who wrote of his journey through Arizona and Mexico in 1861 on the Camino del Diablo or “the road of the devil.” Pumpelly found the territory lawless and filled with danger. Mexican laborers working in the silver mines south of Tucson were perpetually killing their Anglo bosses, and the authorities were virtually non-existent. The Apache led constant raids and ambushes. Pumpelly escaped death several times, often by a matter of minutes. Traveling 130 miles of open desert, he proceeded with both apprehension of the dangers at hand, and appreciation of the natural beauty that surrounded him.

152 years later, Klett traversed the same route, making photographs in response to Pumpelly’s words. Unable to trace the engineer’s exact steps, Klett created images that are not literal references to specific places or events. Rather, he sought to produce a more poetic narrative to their shared experience of the Arizona desert, along the common route that connects the two through time.

Today, most of the Camino is located on the Barry M. Goldwater Bombing Range and the border is a militarized zone constantly patrolled by government agents and crisscrossed by air and ground forces practicing for war. Camino travelers often hide from detection, be they immigrants or drug smugglers moving North under the cover of night or the ruggedness of the terrain. Indian reservations create boundaries and mark other cultural divides. A hostile climate kills many who dare travel in hot weather and people die each year on the Camino, most from exposure. Yet the Camino also crosses one of the most beautiful and still wild regions of the Sonoran Desert.

Limited edition of this book available HERE

ACCOMPANYING LIMITED EDITION

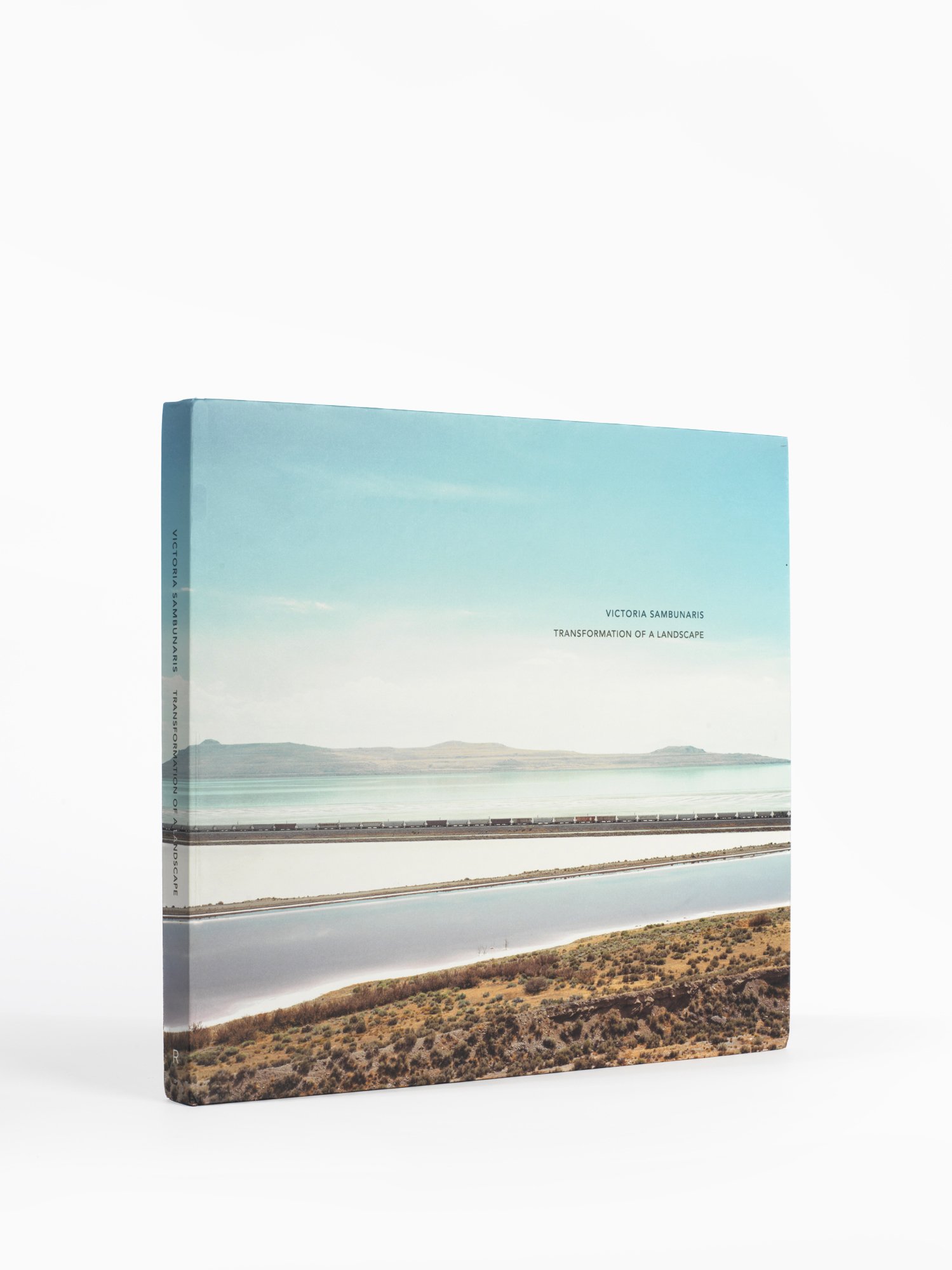

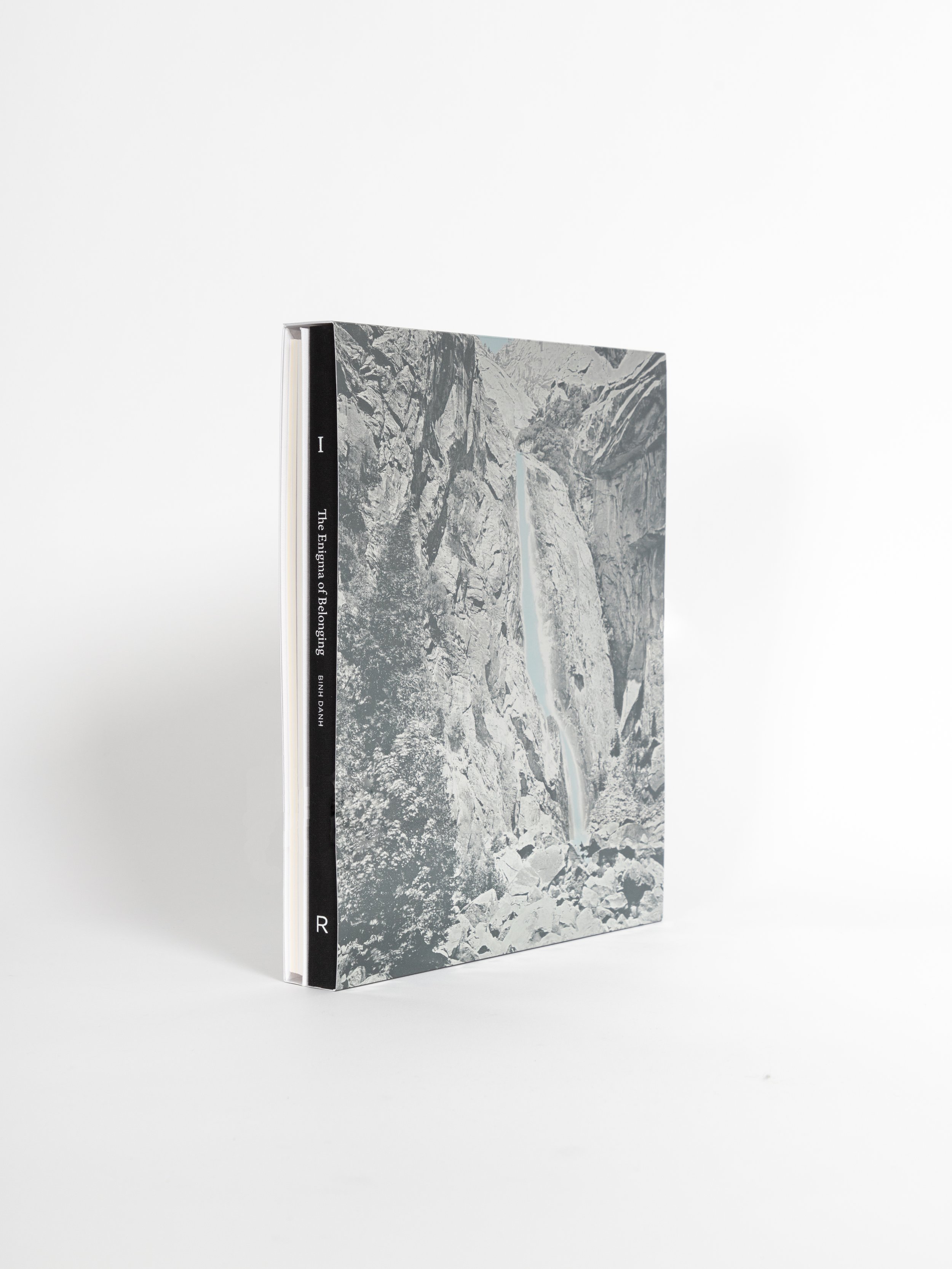

YOU MAY ALSO LIKE

-

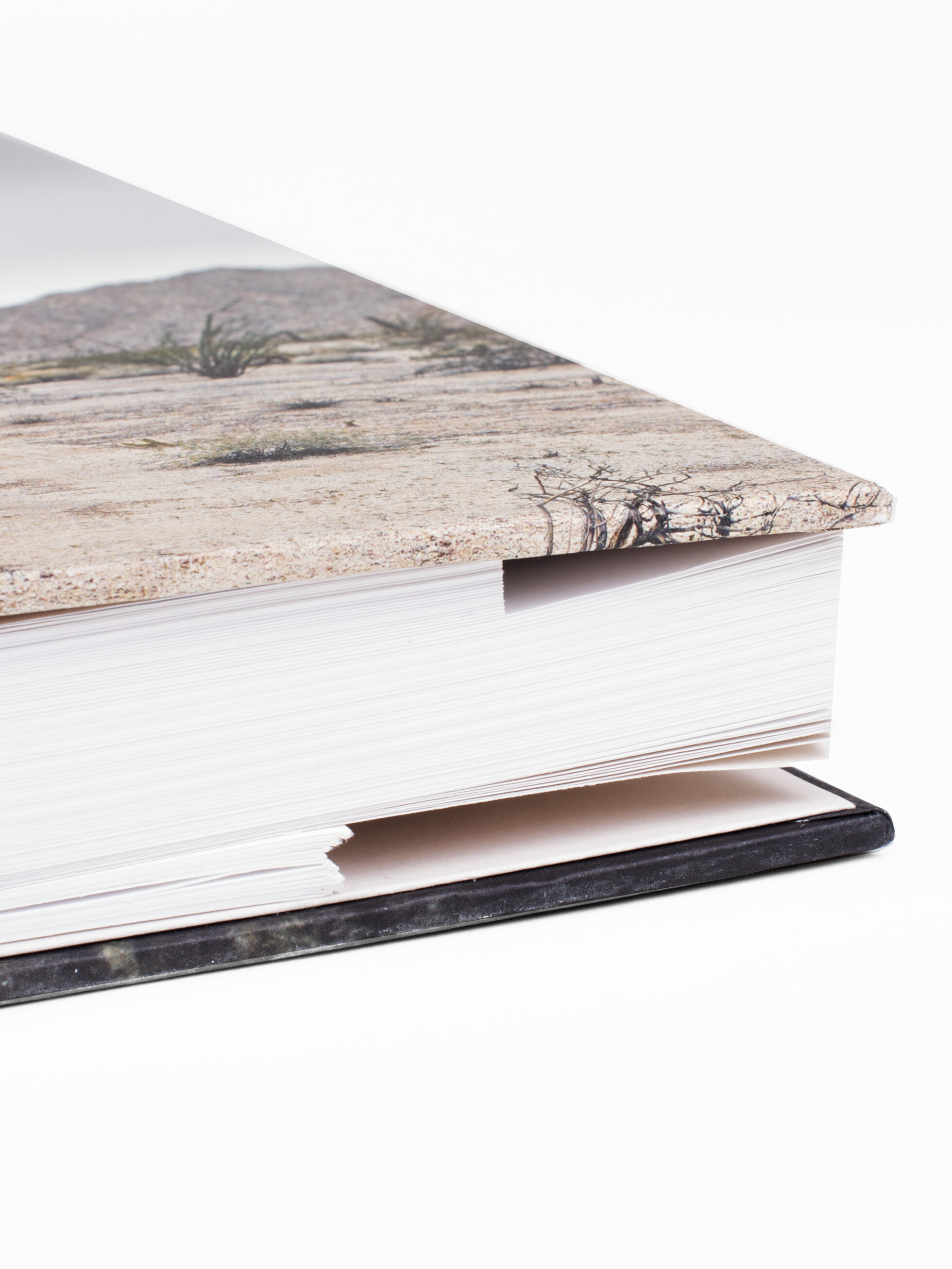

Photographs by Mark Klett

Text by Raphael PumpellyHardcover

10 x 12 inches

172 pages / 60 images

ISBN: 9781942185017 -

Mark Klett is a photographer interested in the intersection of places, history and time. His background includes working as a geologist before turning to photography. Klett has received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Japan/US Friendship Commission. His work has been exhibited and published in the United States and internationally, and is held in over eighty museum collections worldwide. He is the author/co-author of nineteen books including Seeing Time, Forty Years of Photographs (University of Texas Press 2020). Klett is Regents’ Professor Emeritus at Arizona State University.